by Michael Hollister

Published at Geopolitical Monitor on January 14, 2026

2.698 words * 14 minutes readingtime

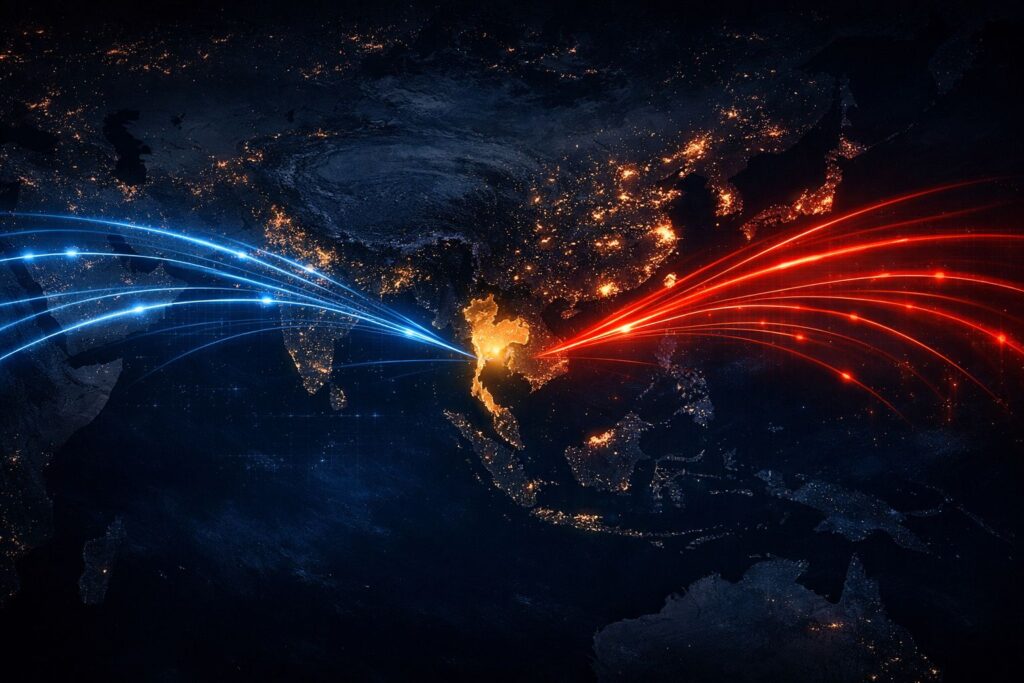

While Europe remains preoccupied with itself, a geopolitical buildup is taking shape in the Indo-Pacific that has long ceased to be mere war-gaming. The third act of the world order won’t premiere in Brussels—but in Chumphon, Ranong, Subic Bay, Guam, and most importantly: Bangkok.

It doesn’t begin with sirens. It begins with treaties. With submarine deliveries, logistics corridors, satellite imagery over the Strait of Malacca. While Europe remains preoccupied with itself, a geopolitical buildup is taking shape in the Indo-Pacific that has long ceased to be mere war-gaming. The third act of the world order won’t premiere in Brussels—but in Chumphon, Ranong, Subic Bay, and Guam.

At the center: Thailand. A country that successfully maneuvered between fronts for decades—and now risks being crushed precisely there.

AUKUS, Armament, and Alliance Formation

Since the founding of AUKUS in September 2021—a security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—strategic densification in the Indo-Pacific has accelerated dramatically. AUKUS is far more than a classical military alliance: it’s a technological defense network focused on nuclear-powered submarines, artificial intelligence, quantum technology, and hypersonic weapons. Australia receives nuclear-powered submarines, Britain deploys parts of its Indo-Pacific fleet to Singapore, and the United States massively expands its presence in the Philippines—four new military bases were agreed in 2024 alone, supplemented by airspace surveillance and electronic warfare systems.

Add to this constant rotations of US ships through the South China Sea and joint exercises with Japan, South Korea, India, and increasingly Vietnam.

China responds—not through parades, but through positioning: dual-use ports in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Pakistan, 5G-controlled command centers along the Silk Road, modernized naval bases on the Paracel and Spratly Islands. The People’s Republic pursues asymmetric dominance: data, infrastructure, economic networks—militarily exploitable, but politically quiet.

The result is a multipolar tension field encircling Southeast Asia like a ring. Thailand sits in the middle—caught between competing visions of the Indo-Pacific’s future order.

Thailand: A Buffer State at Its Tipping Point

Thailand’s decades-long role as neutral mediator between West and East faces pressure. The United States demands clarity—on joint exercises, overflight rights, intelligence cooperation. China demands loyalty—through investments, concessions, and digital infrastructure.

What was once celebrated as strategic ambiguity now becomes a tightrope walk. In a crisis—say, an escalation over Taiwan—Thailand won’t be able to hide behind diplomacy. The decision will be forced, not chosen.

Moreover: Thailand’s geographic location isn’t just central, it’s militarily critical. The land bridge between the Andaman Sea and Gulf of Thailand is already being discussed as potential fallback or supply space for US units—as well as a possible access point for Chinese supply chains and troop movements via Laos. What serves as a trade route in peacetime becomes a strategic lifeline in crisis.

Thailand in a Taiwan Contingency

Most Western analyses underestimate Thailand’s geostrategic role in a Taiwan scenario. While Japan, Guam, and the Philippines form the frontline, Thailand lies in the shadow of this axis—as logistical fallback territory, as bypass corridor, as data and communications hub.

Scenario 1: Strategic Accommodation with the United States

Thailand permits overflight rights, tacit logistics support, or intelligence access. The United States gains what it needs most in the region: a reliable logistics node outside the immediate Taiwan theater, capable of supporting extended operations without exposing forces to direct Chinese counter-strikes.

Result: Immediate escalation with Beijing. Chinese investment—which has dominated Thailand’s infrastructure development for the past decade—collapses overnight. Digital access gets restricted as China cuts off tech partnerships and cloud services. Economic retaliation follows across every sector: agricultural imports face sudden “quality inspections,” tourism operators lose Chinese group bookings that represent billions in annual revenue, and Thai exporters find themselves shut out of mainland markets. The economic pain would be swift and severe, potentially triggering domestic political crisis as business elites—heavily invested in China ties—turn against the government’s decision.

Scenario 2: Withdrawal and Neutrality

Thailand refuses all involvement, doesn’t position itself publicly, blocks access to both sides. Bangkok declares strict neutrality, closes airspace to military flights, and prohibits any intelligence cooperation. On paper, this looks like classic non-alignment. In practice, it satisfies nobody.

Result: Deep distrust from Washington, which views neutrality in a Taiwan crisis as tacit support for Beijing. Military cooperation agreements get frozen or cancelled. Western companies, worried about supply chain security and political risk, begin relocating operations to Vietnam or the Philippines. Thailand’s reputation as a reliable partner—cultivated over decades through military exercises and security dialogues—evaporates. The country becomes what strategists call a “gray zone”—formally independent but functionally irrelevant, bypassed by both sides in their planning. Investment flows dry up not because of sanctions, but because Thailand has made itself invisible at exactly the moment when the region’s future is being decided.

Scenario 3: De Facto Alignment with China

Thailand continues economic cooperation with China, remains politically passive on Taiwan, but indirectly protects Chinese interests through infrastructure policy and digital architecture. Bangkok doesn’t announce an alliance—it simply keeps operating Huawei networks, processing data through Alibaba servers, and maintaining open logistics corridors that happen to serve Chinese supply chain needs. The alignment remains deniable but functional.

Result: Economic stability in the short term, but geopolitical isolation in the long term. Western technology companies withdraw, not through government order but through risk assessment. Access to multilateral development funds becomes complicated as the World Bank and IMF face pressure to reconsider lending profiles. Japan and South Korea—both critical trade partners—begin quiet distancing. Most significantly, Thailand finds itself increasingly dependent on Chinese goodwill for economic survival, with less and less room to maneuver independently. The relationship becomes asymmetric: China needs Thailand, but Thailand needs China more. What starts as pragmatic cooperation hardens into structural dependency. And dependencies, once established, are difficult to reverse.

Each option is a decision with consequences. And none can be reversed once made.

Thailand and the Strait of Malacca

Around one-third of global maritime trade passes through the Strait of Malacca. For China it’s even more critical: over 73-75 percent of all energy imports flow through it—oil from the Middle East, LNG from Qatar, raw materials from Africa. No other trade route is so decisive—and so vulnerable.

The passage is extremely narrow at only 2.7 kilometers at its tightest point (the “Phillip Channel”), heavily trafficked, and easily blockable—whether by a disabled ship, a targeted embargo, or in a crisis through military blockade. China itself has openly called this the “Malacca Dilemma”—the strategic fear that its economy can be choked through this bottleneck at any time.

Control over this passage lies—factually—with the US Navy. The United States maintains access points in Singapore, in the Philippines, in Diego Garcia. Add to this cooperation with Malaysia, satellite surveillance, and—in an emergency—the capability to close this lifeline.

Singapore, Malaysia, India—The Blockade Forces Form Up

In a crisis—say after an escalation over Taiwan—a Western coalition could pull exactly this lever. A stop of Chinese tankers, a targeted inspection, or the threat of blockade would immediately pressure China. No country is economically so dependent on maritime trade—and simultaneously so geographically constricted—as China.

Singapore wouldn’t initiate this step, but would tolerate it. Malaysia would be split. India—as an ascending counterweight power—would welcome it. The United States would have command. And China? Would have no quick answer. It would have to fall back on alternatives.

Thailand: From Transit State to Strategic Link

This is precisely where Thailand enters the picture. From Beijing’s perspective, Thailand isn’t just a partner. It’s an escape route. A back channel. A possibility to circumvent Malacca’s stranglehold—through physical and digital infrastructure, through fiber optic cables, pipelines, high-speed trains.

With the Southern Land Bridge—the planned infrastructure corridor between Chumphon (Gulf of Thailand) and Ranong (Andaman Sea)—a realistic land connection between Pacific and Indian Ocean opens for the first time. Container ships from China could unload in eastern Thailand, their cargo would roll across the country by train or truck—and be reshipped on the other side. Without a single mile through Malacca. Without Western control. Without risk.

For China, this wouldn’t be a prestige solution—but a functional victory. The land bridge remains formally civilian. It’s economically highly effective but packaged as foreign-policy neutral. And yet: it fulfills exactly the strategic purpose China needs. A functioning corridor would defuse the pressure point of Malacca—and make Thailand the key axis of a new logistics order.

The West knows this. Washington, Tokyo, and Delhi observe the project closely—and attempt to steer it through influence, participation, or delay. Because whoever controls the data streams, goods axes, and supply chains between ocean and ocean in the future controls far more than just trade. They control room to maneuver. And dependencies.

Thailand’s Critical Position

Double Vulnerability

But this ascent has its price. For as Thailand becomes the bypass route, it also becomes the target. Should the corridor ever be operationally used in a crisis—say during a Malacca blockade—Thailand would immediately be on the radar of Western intelligence services, hacker groups, perhaps even on the list for economic sanctions.

Simultaneously it would be essential for China—too important to lose. Pressure from both directions would increase. And Thailand would have to decide how far it’s prepared to defend this new status—or give it up if necessary.

Infrastructure as Power

In the logic of great powers, Thailand is a marginal actor. No G7 member, no nuclear power, no veto player in New York or Brussels. And yet this country possesses something decisive for the new world order: location. Connectivity. Infrastructure. And what many nations in the Global South have lost—sovereignty.

This combination makes Thailand something that extends far beyond its geographic scale: a potential gamemaker of the new order. Or—if it decides wrongly—a game piece of rival systems, crushed between data cables, export tariffs, and fear of digital exclusion.

Whoever possessed tanks in the 20th century had control. Whoever possesses fiber optic networks in the 21st has shaping power. This shift in means of power plays into Thailand’s hands. Few other countries in Southeast Asia have built infrastructure so systematically over the past ten years—from smart ports through logistics corridors to digitized customs zones and 5G networks.

What begins today as a transit point becomes tomorrow a geopolitical node. Whoever holds the node keeps options open.

Thailand’s Strategic Choice

The Model of Strategic Ambiguity

Thailand was never a colony—an exception in Southeast Asia. And this historical experience has inscribed itself deeply into the country’s political DNA: whoever doesn’t subordinate must assert themselves diplomatically. This attitude shapes foreign policy to this day.

The consistently practiced strategic ambiguity—the deliberate keeping open of alliance commitments—isn’t weakness. It’s a model. Thailand maneuvers between AUKUS and BRI, between submarine deals and smart city cooperations, between US exercises and Chinese digital platforms. This isn’t about neutrality in the classical sense—but about controlled openness with maximum autonomy.

This ability to not have to commit—while remaining relevant—is perhaps Thailand’s most valuable strategic capital in a fragmented world. But the question becomes urgent: is strategic ambiguity sustainable in a crisis? Or will Thailand need to make a fundamental choice about which system it belongs to?

The Critical Window: Two to Three Years

Bangkok perhaps has two to three years left to prepare this positioning—time to build genuine multilateral partnerships, diversify economic dependencies, and establish itself as indispensable to both sides not through alignment, but through unique capabilities. Time to transform geographic centrality into political agency. Time to develop what no amount of military hardware can provide: strategic irreplaceability.

After that window closes, decisions will be made—with or without Thailand. The infrastructure will be built, the alliances will be formalized, the data cables will be laid, and the security architectures will be locked in. Countries that positioned themselves early will have leverage. Countries that hesitated will have regrets.

From Platform to Player

The decisive question is: Does Thailand want to be platform—or partner? Corridor—or node? Mediator—or spectator?

If Thailand manages to transform its geographic potential into political initiative—through ASEAN mediation formats, own dialogue platforms, or a more active role in emerging multipolar architectures—then it could form a new type of balancing power. Not as a great power. But as an indispensable intermediary in a divided world.

Thailand has the potential:

- It’s not a special case like Singapore, but a territorial state with real population and regional influence

- It’s not an ideological exporter like China or the West, but pragmatic, experience-based, culturally sensitive

- It’s not an indebted BRI vassal, but a country with its own economic axis, own innovative capacity, own elite

But this path isn’t inevitable. The greatest danger isn’t external threat—but internal complacency. A Thailand that rests on its geostrategic location will sooner or later be overtaken—not militarily, but structurally. Digital dependencies, fragmented political institutions, a paralyzing dualism between military and civil society—all this could lead to Thailand remaining formally independent but drifting rudderless in the wind of great powers.

The Warning from Asia

The Pacific buildup isn’t coming. It’s here. The question is no longer whether—but when.

From Infrastructure Decision to War Decision

What counted yesterday as an economic question—smart ports, fiber optic networks, highways—becomes today a security policy junction. And Thailand must grasp: whoever owns infrastructure no longer makes neutral decisions. But will be asked—under pressure if necessary, from both sides if necessary—to whom this infrastructure belongs in a crisis.

This is the real warning from Asia: not the escalation is dangerous. But the hesitation before it.

The Front of the Future No Longer Runs Through Berlin or Kyiv

While Europe still wrestles with itself—with migration questions, energy insecurity, party-political trench warfare—the center of gravity of world order has long shifted eastward. Not as sudden explosion, but as tectonic drift. What’s planned in Washington, built in Beijing, and negotiated in Singapore no longer concerns just containers—but conflicts.

For in case of a Taiwan conflict, a Malacca blockade, a cyberattack on global logistics systems—then decisions won’t only be made in the United States or China. But also in Thailand: Do we open the corridor? Do we let data streams through? Who gets access to which infrastructure?

Last Chance: Balance Through Awareness

Thailand was never a colony—and needn’t become one in the 21st century either. But whoever wants to remain neutral must move. Whoever wants to be a gamemaker can’t hide. And whoever doesn’t want to be a piece on the new chessboard of the Indo-Pacific—must become a player.

The window is narrow. Bangkok must decide: strategic accommodation, enforced neutrality, or de facto alignment. Each path has consequences that cannot be reversed.

Thailand may throw no bombs. Send no fleets. Announce no alliances. And yet: the decision over war and peace in the region will also be made there—in Chumphon, in Bangkok, in the digital backend of a data center whose server structure is Chinese-built.

The only question is whether Thailand will help write the next chapter—or simply appear in it as a footnote.

Diese Analyse ist frei zugänglich – aber gute Recherchen kosten Zeit, Geld, Energie und Nerven. Unterstützen Sie mich, damit diese Arbeit weitergehen kann.

Oder unterstützen Sie mich auf Substack – schon ab 5 USD pro Monat.

Gemeinsam bauen wir eine Gegenöffentlichkeit auf.

Michael Hollister is a geopolitical analyst and investigative journalist. He served six years in the German military, including peacekeeping deployments in the Balkans (SFOR, KFOR), followed by 14 years in IT security management. His analysis draws on primary sources to examine European militarization, Western intervention policy, and shifting power dynamics across Asia. A particular focus of his work lies in Southeast Asia, where he investigates strategic dependencies, spheres of influence, and security architectures. Hollister combines operational insider perspective with uncompromising systemic critique—beyond opinion journalism. His work appears on his bilingual website (German/English) www.michael-hollister.com, at Substack at https://michaelhollister.substack.com and in investigative outlets across the German-speaking world and the Anglosphere.

© Michael Hollister— Redistribution, publication or reuse of this text is explicitly welcome. The only requirement is proper source attribution and a link to www.michael-hollister.com (or in printed form the note “Source: www.michael-hollister.com”).

Newsletter

🇩🇪 Deutsch: Verstehen Sie geopolitische Zusammenhänge durch Primärquellen, historische Parallelen und dokumentierte Machtstrukturen. Monatlich, zweisprachig (DE/EN).

🇬🇧 English: Understand geopolitical contexts through primary sources, historical patterns, and documented power structures. Monthly, bilingual (DE/EN).